The pursuit of efficient solar energy harvesting presents a stark contrast between terrestrial and orbital environments. While terrestrial solar farms are the backbone of current renewable infrastructure, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) arrays offer a high-intensity, uninterrupted alternative that fundamentally shifts the math of energy production.

Solar Irradiance and Atmospheric Attenuation

The most significant disparity begins at the top of the atmosphere. In LEO, solar panels are exposed to the “solar constant”—approximately 1,361 Watts per square meter (W/m²) of unfiltered radiant power. This energy is pristine, containing the full spectrum of solar radiation.

In contrast, terrestrial solar farms must contend with atmospheric attenuation. As sunlight passes through the Earth’s atmosphere, it is subjected to scattering and absorption by water vapor, greenhouse gases, and aerosols. On a clear, dry day, the direct normal irradiance (DNI) at the surface rarely exceeds 1,000 W/m². When factoring in cloud cover and air pollution, terrestrial systems can lose 55% to 60% of incident energy before it even reaches a photovoltaic cell.

Capacity Factors and Intermittency

Efficiency in energy capture is not just about peak power; it is about duration. Terrestrial solar farms suffer from an inherent “capacity factor” limitation due to the diurnal cycle and weather. A typical high-performance solar farm in the Mojave Desert averages about 5 to 9 full-sun-equivalent hours per day.

LEO orbital arrays, however, can be positioned to remain in nearly constant sunlight. Depending on the altitude and inclination (such as a sun-synchronous “terminator” orbit), a satellite can collect power for 99% of the year. NASA and JAXA studies suggest that an orbital solar plant can generate upwards of 13 times more energy annually than an identical installation on the ground because it bypasses night and weather entirely.

Photovoltaic Conversion and Specific Power

The hardware used in these two environments reflects their different constraints:

- Terrestrial Arrays: Primarily use single-junction silicon cells. These are cost-effective and mass-produced but are limited to 20–25% efficiency.

- LEO Arrays: Utilize advanced multi-junction cells, often made of Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) or Indium Phosphide (InP). These “space-grade” cells can achieve 40–50% efficiency in 2026-era designs.

Furthermore, space engineers prioritize specific power (Watts per kilogram). High-efficiency, thin-film flexible arrays, such as those developed by Solestial or Rocket Lab, target power-to-mass ratios exceeding 500–800 W/kg. This is critical for LEO, where the cost of launch is a primary bottleneck.

Summary of Efficiency Metrics

| Metric | Terrestrial Solar Farm | LEO Orbital Array |

| Incident Irradiance | ~1,000 W/m² (Peak) | ~1,361 W/m² (Constant) |

| Cell Efficiency | 20–25% (Silicon) | 40–50% (Multi-junction) |

| Capacity Factor | 20–30% (Weather/Night) | >95% (Near-continuous) |

| Energy Yield | 1x Baseline | ~13x Terrestrial Baseline |

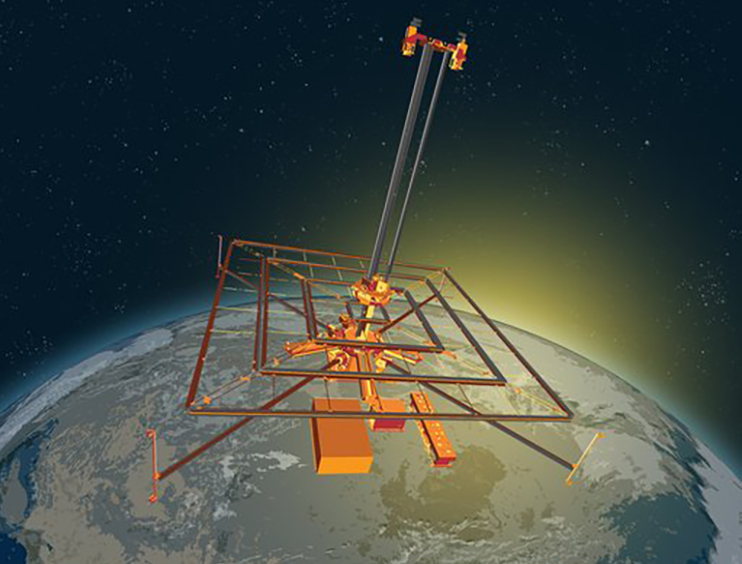

While LEO arrays are vastly more efficient at capturing energy, they face the unique challenge of transmitting it. Unlike terrestrial systems connected to a physical grid, orbital arrays must convert electricity into microwaves or lasers to beam power to Earth, introducing conversion losses that terrestrial systems avoid. Despite this, as launch costs drop via platforms like Starship, the orbital “solar gain” is becoming an increasingly viable solution for global baseload power.