Why the Road to the Orbital Cloud Data Center Runs Through a SmallSat

SatNews Editorial Analysis

Before we dream of floating data centers, we must understand why the SmallSat is the only laboratory that matters.

As the industry prepares for the SmallSat Symposium, we stress-test one of space’s buzziest ideas, orbiting computing, against the unforgiving constraints of SmallSats.

Welcome to The Fractal Lab: a three-part series on why orbital computing succeeds or fails first at 10 kilograms, not 10,000.

Part 1: The Physics Trap

Why Space is the Worst Place for a Data Center

Regardless of location, every data center has a simple, brutal metabolism: it devours electricity and excretes heat. For every watt of power pumped into a bank of servers, nearly a watt of waste heat is generated. The engineering challenge is never just about computing; it is about keeping the machine from melting itself.

The engineering challenges facing a hypothetical gigawatt-scale Orbital Data Center (ODC) are not new. They are simply fractal versions of the thermal bottlenecks already constraining high-performance SmallSats. While the industry imagines massive floating buildings, engineering teams struggling to reject hundreds of watts from compact spacecraft buses are inadvertently validating the technologies a future megawatt-class economy would require.

But before we discuss orbits or bandwidth, we must confront the single hardest truth of orbital engineering: Space is not cold. It is a thermos.

To appreciate this, we must first strip away the science fiction to define exactly where this machine lives and why it is so difficult to prevent thermal runaway.

The Location Problem

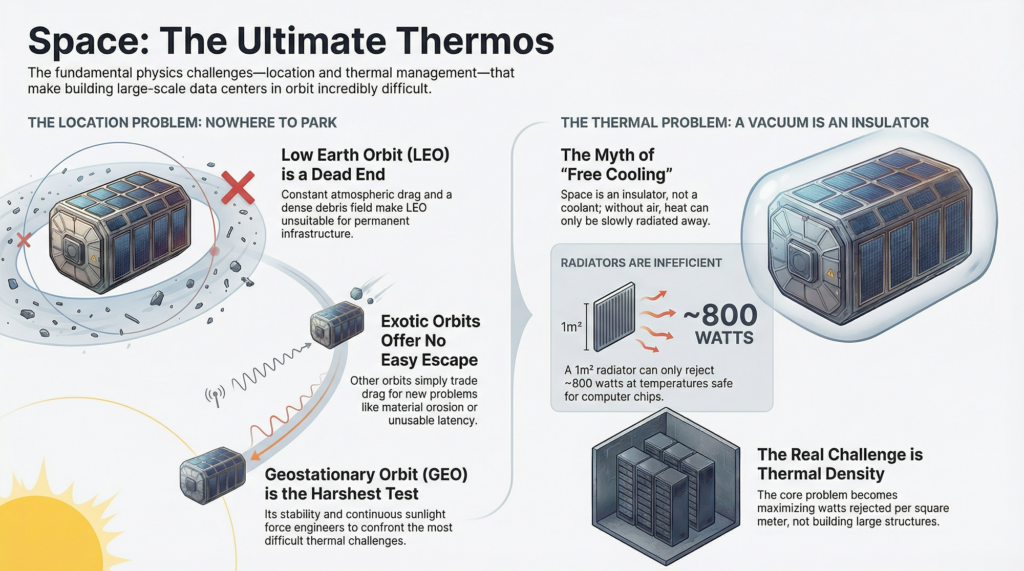

When we discuss placing infrastructure in space, we are really choosing between a specific menu of orbital regimes: Low Earth Orbit (LEO), Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), Geostationary Orbit (GEO), or even exotic deep-space points. But the laws of physics and economics quickly filter this list down.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO), despite its proximity, is likely a dead end for permanent, megawatt-scale infrastructure. At 400 kilometers, atmospheric drag on massive solar arrays demands constant re-boosting, while the debris environment drives insurance premiums to prohibitive levels.

Some engineers argue that Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO), altitudes below 250 km, could solve this. By utilizing aerodynamic shaping and air-breathing propulsion, satellites could theoretically fly in self-cleaning orbits where debris naturally decays. However, VLEO trades drag for atomic oxygen erosion, a material science nightmare that swaps a propulsion bill for a structural maintenance one.

This leads many to propose Highly Elliptical Orbits (HEO) or cislunar space. These orbits offer distinct advantages: they can reduce radiation exposure compared to the Van Allen belts or provide long dwell times over specific hemispheres. Some even argue for the Earth–Sun Lagrange points (L2) to escape Earth’s infrared glow entirely. Moving to L2 solves the thermal environment but exacerbates latency and link-budget issues to the point of uselessness for commercial applications.

However, these orbits trade away what Geostationary Orbit (GEO) makes brutally clear: permanent exposure to the hardest constraints. We focus on GEO not because it is the only option, but because it is the most honest stress test.

In GEO, the drag is zero and sunlight is near-continuous, interrupted only by seasonal eclipse periods. However, GEO slots are a finite, ITU-regulated resource. You cannot simply park a gigawatt data center wherever you please; obtaining a slot is a multi-year geopolitical hurdle that adds significant deployment risk. Furthermore, while the orbit is stable, the thermal price tag is one that terrestrial engineers rarely comprehend.

The Myth of Free Cooling

Cooling is the defining constraint of every data center, terrestrial or orbital. On Earth, engineers solve this by dumping heat into the atmosphere or local water sources using convection—fans blowing air or pumps circulating coolant. But once we leave the atmosphere, we lose the medium that makes cooling easy.

With the location defined, we encounter the most persistent myth in the industry: that space is the perfect place for data centers because “space is cold.”

This is a dangerous oversimplification. Space is not a coolant; it is an insulator. In a vacuum, convection (the mechanism that cools every terrestrial server) does not exist. Fans are useless. Heat rejection is dominated entirely by radiation, which scales with the fourth power of temperature but remains far less efficient than convection at equivalent temperatures.

The Stefan–Boltzmann Law governs everything. A one-square-meter radiator operating at 350 K (77 °C) rejects approximately 700–850 watts, depending on emissivity. To double that rejection, one must either double the radiator area or raise the operating temperature to roughly 400–420 K (125–145 °C), hot enough to induce thermal runaway or unacceptable reliability degradation in commercial silicon.

This transforms the problem from civil engineering (“how do we build large structures in zero gravity?”) into thermal-density optimization. How do we maximize watts rejected per square meter at silicon-safe temperatures?

Even the nuclear option, replacing massive solar arrays with compact fission reactors, does not escape this trap. While nuclear power solves the energy generation density, it does nothing to solve the heat rejection density. Every watt of computation still produces a watt of waste heat that must be radiated away. If we cannot close the thermal loop on a 50-kilogram spacecraft, we will never close it on a 50,000-kilogram station.

Coming Up:

If the physics of cooling is this difficult, surely the unique data capabilities of orbit justify the effort? In Part 2, we examine the “Data Gravity” problem and why moving bytes might be harder than moving heat.