By Evan Grey, Legal Contributor, SatNews

The primary battleground for space supremacy has shifted. While the world watches the launchpads, the decisive contest is unfolding inside the filing processes of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

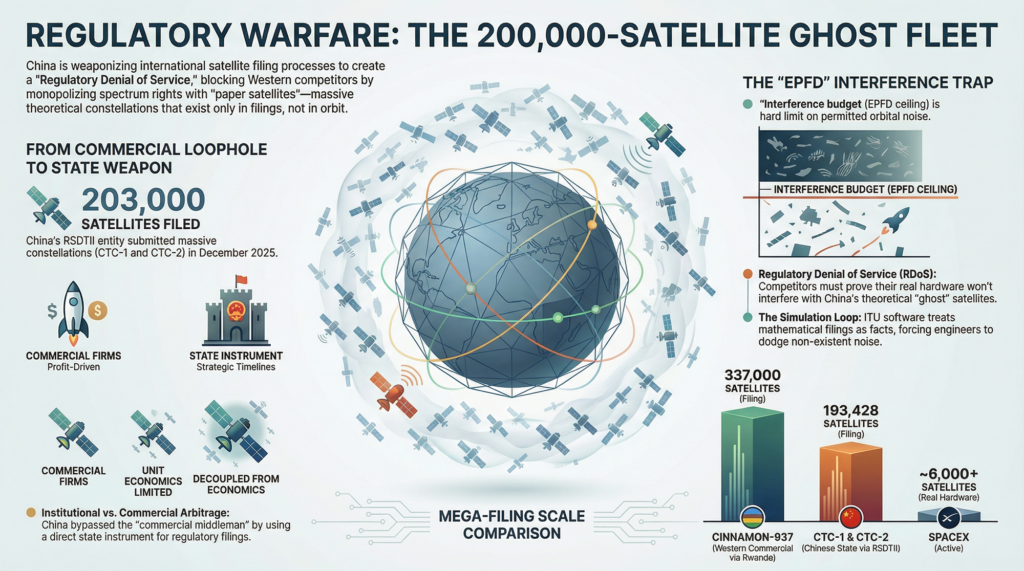

In the final week of December 2025, China submitted a batch of NGSO filings totaling roughly 203,000 satellites. The lion’s share, 193,428 satellites, was attributed to a new entity, the Institute of Radio Spectrum Utilization and Technological Innovation (RSDTII), under two constellations, CTC-1 and CTC-2.

The scale alone makes clear this is not a near-term deployment plan. It is a strategic attempt to establish regulatory priority at a level capable of slowing, complicating, and reshaping competitors’ future deployments.

From Commercial Exploit to State Weapon

The ITU filing system was designed for commercial operators seeking profit. In that model, investors demand returns, and market forces eventually weed out speculative claims that never materialize into revenue-generating networks.

However, the West pioneered the weaponization of this process. Western operators utilized regulatory arbitrage by using small administrations, most famously Tonga, as filing vehicles to secure early coordination priority. The Cinnamon-937 filing, a 337,000-satellite constellation filed via Rwanda in 2021, demonstrated that the ITU’s system could be gamed at extraordinary scale. China did not invent regulatory flooding; they simply industrialized a blueprint drafted by Western speculators.

A Critical Distinction Remains: Western mega-constellations, despite defense contracts blurring lines between commercial and strategic, remain tethered to unit economics. Even SpaceX must eventually show a path to solvency. Failure has a cost.

China has simply scaled what Western operators pioneered but removed the commercial middleman. Where Western entities used Rwandan or Tongan regulatory flags, China established RSDTII as a direct state instrument. Notably, RSDTII was formally registered in the Xiong’an New Area on December 30, 2025 one day after the filings were submitted. The mechanics are identical to Western speculation, but the institutional backing differs. Western mega-filings remain tethered to eventual investor expectations; state-backed filings answer only to strategic timelines that can stretch across decades.

The EPFD Trap: Weaponizing Interference Budgets

The lethality of this strategy is not merely about physical orbital slots; it is about the weaponization of Equivalent Power Flux Density (EPFD) limits.

Under ITU Article 22, NGSO systems like Starlink or Amazon Kuiper must ensure their aggregate radio emissions do not cause “unacceptable interference” to higher-priority Geostationary (GSO) satellites. This creates a finite “interference budget”—a hard ceiling on how much radio noise is permitted in a given frequency band.

By filing for nearly 203,000 satellites, RSDTII is effectively reserving a massive portion of this interference budget. The CTC-1 and CTC-2 filings likely include aggressive “PFD masks” theoretical emission profiles that claim vast amounts of the available spectrum capacity.

This creates a Regulatory Denial of Service. Even if China never launches a single satellite, their filing forces every subsequent Western operator to prove that their new satellites will not push the total interference over the “EPFD cliff” when added to China’s theoretical massive constellation. Western engineers are forced to design real hardware to dodge the “ghost noise” of Chinese paper satellites, effectively throttling the power and performance of U.S. networks before they even launch.

The Access Question We’ve Been Avoiding

China’s framing of this as a “Global South equity issue” is cynical, but it is also strategically effective.

The current reality is stark. The United States and its commercial allies are rapidly filling the most valuable LEO orbital regimes. SpaceX alone has more active satellites than the rest of the world combined. The ITU’s time-priority coordination framework, combined with Western launch dominance, creates a de facto lock-in where the rules-based order conveniently secures American advantage.

When Western policymakers defend “first-mover rights” at WRC-27, they will be defending a system that has, in practice, reserved the best orbital real estate for those who could afford rapid deployment in the 2020s. That is not technical neutrality; it is incumbency protection with a technical veneer.

This doesn’t make China’s 203,000-satellite filing legitimate. But it does mean the West cannot simply invoke rules-based order without acknowledging that those rules are producing profoundly asymmetric outcomes.

The Governance Crisis: When Commercial Rules Meet State Power

The mechanism of this squatting is insidious because the ITU validation software treats these filings as mathematical facts. When China submits data claiming 193,000 satellites will operate at specific power levels, the software calculates interference based on that input without asking if launch capacity exists.

Consequently, Western operators are trapped in a simulation loop. They must coordinate against a mathematical model that claims to occupy the entire noise floor. To the ITU’s computers, the interference from a “paper satellite” is just as real as the interference from a real one. The 2027 World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC-27) is no longer a routine technical meeting; it is the decisive arena where these rules of the road will be rewritten.

Why Isn’t the U.S. Filing for 500,000 Satellites?

The most revealing question about this situation is the one being avoided: If ITU filings are this powerful, cheap, and strategically important, why hasn’t the U.S. government filed for massive constellations through NASA or the Space Force?

The answer reveals the limits of state action in the Western model:

- Institutional Friction: There is genuine resistance to the idea that the U.S. government should directly compete with American commercial entities. A USSF mega-filing would seem either redundant or competitive to Starlink and Kuiper.

- Liability & Hypocrisy: Western governments are sensitive to the narrative of orbital sustainability. A U.S. state filing for half a million satellites would be a diplomatic nightmare, contradicting every American pledge regarding debris mitigation.

- The Exposure Problem: If the U.S. filed through a government entity and then failed to deploy, the reputational cost would be immediate and public. Congressional hearings and GAO audits create friction that makes speculative filing politically expensive. China’s RSDTII can file for 200,000 satellites and quietly re-scope without public accountability.

Conclusion: The End of Technical Neutrality

For decades, the ITU has maintained the fiction that spectrum coordination is a purely technical matter, politically neutral, and commercially agnostic. The RSDTII filing disrupts that illusion.

When state actors weaponize technical safety margins like EPFD limits to enforce geopolitical blockades, technical neutrality becomes complicity. The West pioneered regulatory arbitrage in space and is now discovering that loopholes exploited for profit become weapons when exploited for power.

About the Author:

Evan Grey is a legal contributor for SatNews. A lawyer with a focus on regulatory policy and international relations, he specializes in the evolving geopolitical and industrial frameworks of the global space sector.