Disrupts CubeSat Standards

The successful deployment of four DiskSat spacecraft during Rocket Lab’s “Don’t Be Such A Square” mission represents far more than a simple hardware iteration; it is a structural challenge to the legacy constraints of small satellite design.

For over two decades, the CubeSat standard—defined by its rigid 10-centimeter units—governed the democratization of space. While revolutionary, the CubeSat’s boxy geometry inherently limited the surface area available for power generation and aperture size, often necessitating complex, failure-prone deployable mechanisms for solar panels and antennas.

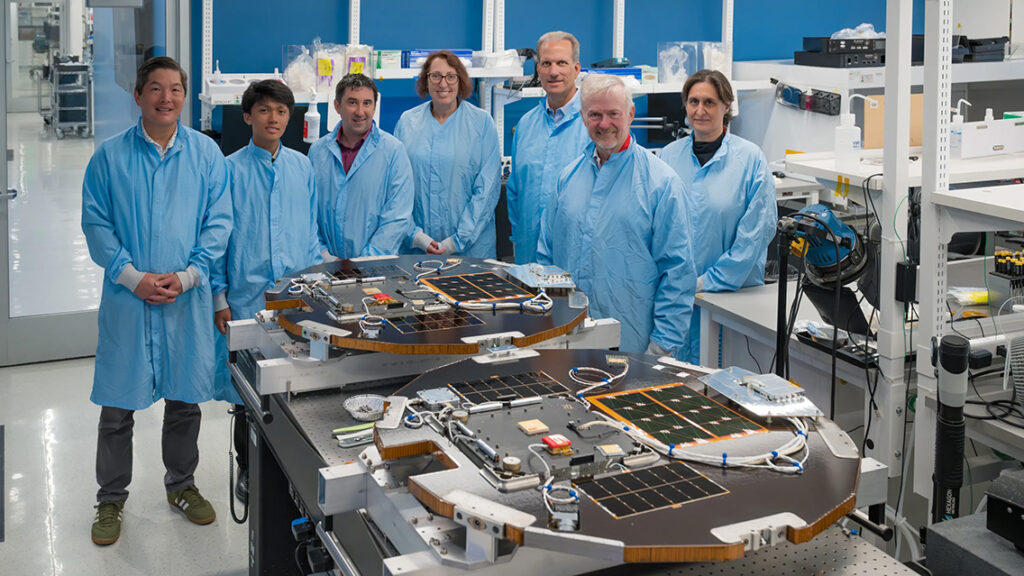

The DiskSat platform, a collaborative effort between NASA and The Aerospace Corporation, breaks this “cube” paradigm by introducing a circular, plate-like form factor that measures one meter in diameter while remaining only 2.5 centimeters thick. By prioritizing surface area over volume, DiskSat offers a superior power-to-mass ratio and internal real estate for instruments, effectively solving the “energy starvation” problem that plagues traditional nanosatellites without requiring the mass and mechanical complexity of traditional folding arrays.

This shift in geometry is the primary catalyst for the “Assembly Line” trend in regulatory and industrial modernization. The transition from bespoke, artisanal satellite integration to a high-volume manufacturing model requires standardized hardware that is optimized for “packing efficiency.”

Because DiskSats can be stacked like dinner plates within a launch vehicle’s fairing, they allow launch providers to maximize the use of available volume, potentially carrying dozens or even hundreds of units in a single mission without the parasitic mass of heavy deployment racks.

This standardization is the hardware prerequisite for a Licensing Assembly Line. When the physical characteristics of a satellite are uniform and predictable, the regulatory hurdles—ranging from collision risk assessments to electromagnetic interference clearances—can be processed through automated, high-speed channels rather than the current months-long manual reviews. This creates a feedback loop where standardized hardware drives regulatory efficiency, which in turn lowers the barrier to entry for mega-constellations.

Beyond manufacturing efficiency, the DiskSat platform serves as the technological vanguard for Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO) operations, a domain critical to the sustainability of the orbital environment. Operating at altitudes below 300 kilometers offers significant advantages for Earth observation and telecommunications, including reduced latency and higher resolution with smaller sensors.

However, the residual atmosphere at these altitudes creates significant drag, which usually causes satellites to deorbit rapidly. DiskSat’s unique aerodynamics allow it to fly “edge-on” into the atmospheric flow, minimizing drag while maximizing the surface area available for solar energy to power electric propulsion systems. This enables persistent flight in a region of space that was previously considered a “transient” zone.

The strategic importance of VLEO integration cannot be overstated regarding space debris mitigation. Because the atmosphere is dense enough to ensure rapid, natural reentry once a mission concludes or a satellite fails, DiskSat eliminates the risk of long-term orbital “zombies” that haunt higher altitudes. This alignment with sustainability metrics ensures that as the volume of space traffic increases, the risk of Kessler Syndrome—a cascading collision event—is naturally mitigated by the physics of the orbit itself. Consequently, the DiskSat launch is not merely a successful flight test; it is the validation of a new architectural blueprint for the space economy, moving away from the “square” limitations of the past toward a flat, scalable, and sustainable future.