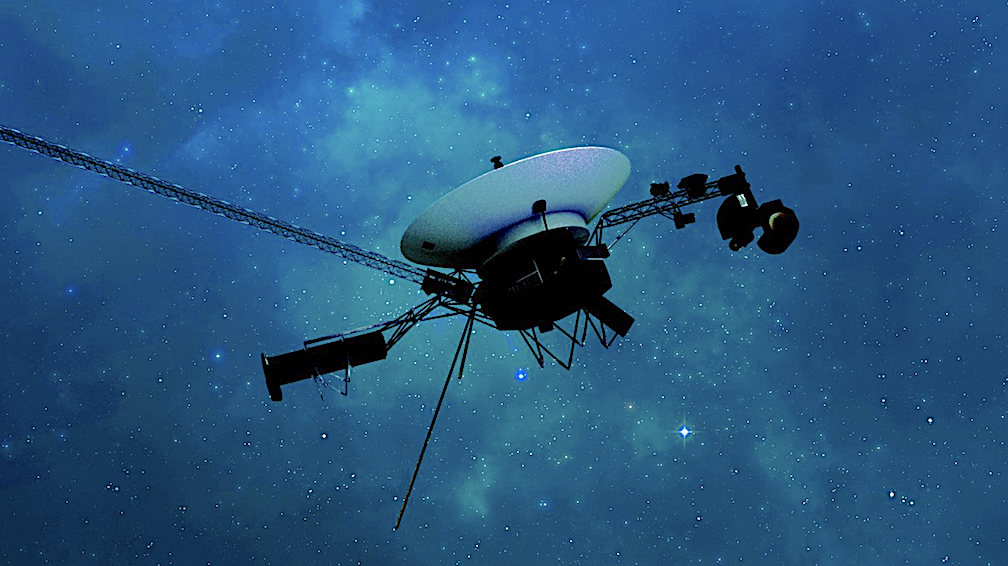

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

After some inventive sleuthing, the mission team can — for the first time in five months — check the health and status of the most distant human-made object in existence.

For the first time since November, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems. The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again. The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between stars).

Voyager 1 stopped sending readable science and engineering data back to Earth on November 14, 2023, even though mission controllers could tell the spacecraft was still receiving their commands and otherwise operating normally. In March, the Voyager engineering team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California confirmed that the issue was tied to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, called the flight data subsystem (FDS). The FDS is responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it’s sent to Earth.

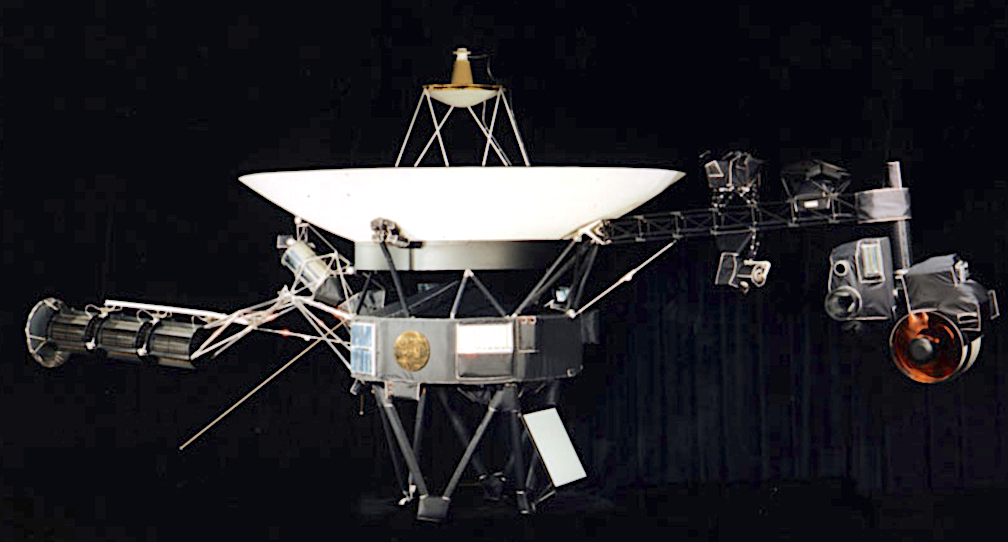

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

More about the above photo:

In a conference room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, members of the Voyager mission team gathered April 20, 2024, to find out if an issue on Voyager 1 had been partially resolved. Just after 6:40 a.m., a cheer went up around the room as the group heard back from the spacecraft: It was returning engineering data for the first time since November 2023.

Nearly two full days earlier, the team had sent a series of commands to move a section of software code used by the flight data subsystem (FDS) computer to a new location. The physical location where the code was previously stored has been damaged, causing the mission to go five months without receiving science or engineering data. But the commands were a success, and the team received data about the health and status of the spacecraft, prompting celebration.

The commands were sent on April 18, 2024. Due to Voyager 1’s distance from Earth – over 15 billion miles or 24 billion kilometers – a radio signal takes about 22 ½ hours to travel to the spacecraft, and 22 ½ hours to return to Earth.

Shown are Voyager team members Kareem Badaruddin, Joey Jefferson, Jeff Mellstrom, Nshan Kazaryan, Todd Barber, Dave Cummings, Jennifer Herman, Suzanne Dodd, Armen Arslanian, Lu Yang, Linda Spilker, Bruce Waggoner, Sun Matsumoto, and Jim Donaldson.

In a conference room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, members of the Voyager mission team gathered April 20, 2024, to find out if an issue on Voyager 1 had been partially resolved. Just after 6:40 a.m., a cheer went up around the room as the group heard back from the spacecraft: It was returning engineering data for the first time since November 2023.

Nearly two full days earlier, the team had sent a series of commands to move a section of software code used by the flight data subsystem (FDS) computer to a new location. The physical location where the code was previously stored has been damaged, causing the mission to go five months without receiving science or engineering data. But the commands were a success, and the team received data about the health and status of the spacecraft, prompting celebration.

The commands were sent on April 18, 2024. Due to Voyager 1’s distance from Earth – over 15 billion miles or 24 billion kilometers – a radio signal takes about 22 ½ hours to travel to the spacecraft, and 22 ½ hours to return to Earth.

Shown are Voyager team members Kareem Badaruddin, Joey Jefferson, Jeff Mellstrom, Nshan Kazaryan, Todd Barber, Dave Cummings, Jennifer Herman, Suzanne Dodd, Armen Arslanian, Lu Yang, Linda Spilker, Bruce Waggoner, Sun Matsumoto, and Jim Donaldson.

The team discovered that a single chip responsible for storing a portion of the FDS memory — including some of the FDS computer’s software code — isn’t working. The loss of that code rendered the science and engineering data unusable. Unable to repair the chip, the team decided to place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety.

So they devised a plan to divide the affected code into sections and store those sections in different places in the FDS. To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole. Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well.

The team started by singling out the code responsible for packaging the spacecraft’s engineering data. They sent it to its new location in the FDS memory on April 18. A radio signal takes about 22 ½ hours to reach Voyager 1, which is over 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, and another 22 ½ hours for a signal to come back to Earth. When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft.

During the coming weeks, the team will relocate and adjust the other affected portions of the FDS software. These include the portions that will start returning science data.

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally. Launched over 46 years ago, the twin Voyager spacecraft are the longest-running and most distant spacecraft in history. Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.